Interview | What Time Is It Now:

Zhang Kailai

22/05/2025

This June, Momingtang will present the exhibition What Time Is It Now at its London space. Featuring moving image works by four artists—Zhang Kailai, Wang Xuehan, Wei Wentao, and Shi Hui—the exhibition seeks to explore the possible alternative forms of time, a concept that is vast, ancient, and yet intimately tied to our everyday lives.

In these artists’ works, time is no longer a linear thread. It is sliced, collaged, compressed, and then unfolded. Through this process, we witness how narratives shift and how so-called reality begins to loosen. To imagine other forms of time is also to imagine other ways of living. In this sense, the exhibition asks: If time is not linear, how might we reinterpret the events in our lives? If concepts such as “past” and “future” are not as fixed as we tend to believe, how might our emotions shift—and how else might we live?

This series of features will present our interviews with the four participating artists. Each of them, in their own way, disrupts reality. In our conversations, they share how those disruptions take place.

Zhang Kai Lai

(b.1999) is an interdisciplinary artist and photographer. She graduated from University of International Relations and the Royal College of Art. Her work has been exhibited in various countries including China, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, and South Korea.

Her creative practice focuses on memory, time, and emotion, often employing film and experimental techniques in her explorations. Rooted in diverse philosophical reflections, her work captures fleeting moments of beauty and invites viewers to embark on a journey of sensing the self and the world in motion.

Q1: What time is it now?

Zhang Kailai: 19:30 (GMT+8).

Q2: Generally speaking, what’s your favorite time of day? What do you usually do during that time?

Zhang Kailai: I like the quiet, undisturbed late night hours. Most people’s work and daily routines happen during the day, so night seems to have become, by unspoken consensus, a time reserved for oneself. I often stay up late as a form of “revenge bedtime procrastination”—thinking about things I didn’t manage to figure out during the day, or doing things I wanted to do but didn’t have time for.

Q3: From your personal life experience and individual perception, in what way does time flow?

Zhang Kailai: As humans, we tend to use things we already understand—especially things that are more tangible—to try to make sense of things we can’t directly see or touch. So most of the time, when we talk about “time,” we’re describing it in spatial terms, like “looking ahead.”

To me, time may not be something that can truly be measured using spatial definitions, but spatial concepts can certainly help us understand or describe it. When we fix our gaze on a particular moment, time can be frozen. When we focus on a certain sequence, time can unfold as a linear narrative.

In experiences of loss or similar moments, we often become more acutely aware of the existence of time—for instance, we only realize we’ve gone through a span of time once something has ended.

Q4: When did you first become interested in photography? And how did your path as an artist begin?

Zhang Kailai: My grandfather had a darkroom at home, so I became interested in photography at a very young age. But back then, I didn’t explore much with film or the darkroom, because my family never really supported me pursuing art—as someone from Shandong, they probably expected me to follow a more stable path through education and employment.

Given that, I chose a major related to economics for my undergraduate studies. I was in an environment where hardly anyone was involved in artistic creation, so I had to explore on my own. During university, I spent a lot of time taking photos, and through repeated experimentation I gained a deeper understanding of art and the industry. I gradually started taking on some part-time jobs related to photography and media, and through that process I began to realize that maybe I could actually study and work in photography. Eventually, I switched fields and pursued a photography master’s degree at the Royal College of Art.

Untitled, 2021

Untitled,2021

Untitled, 2021

Untitled, 2021

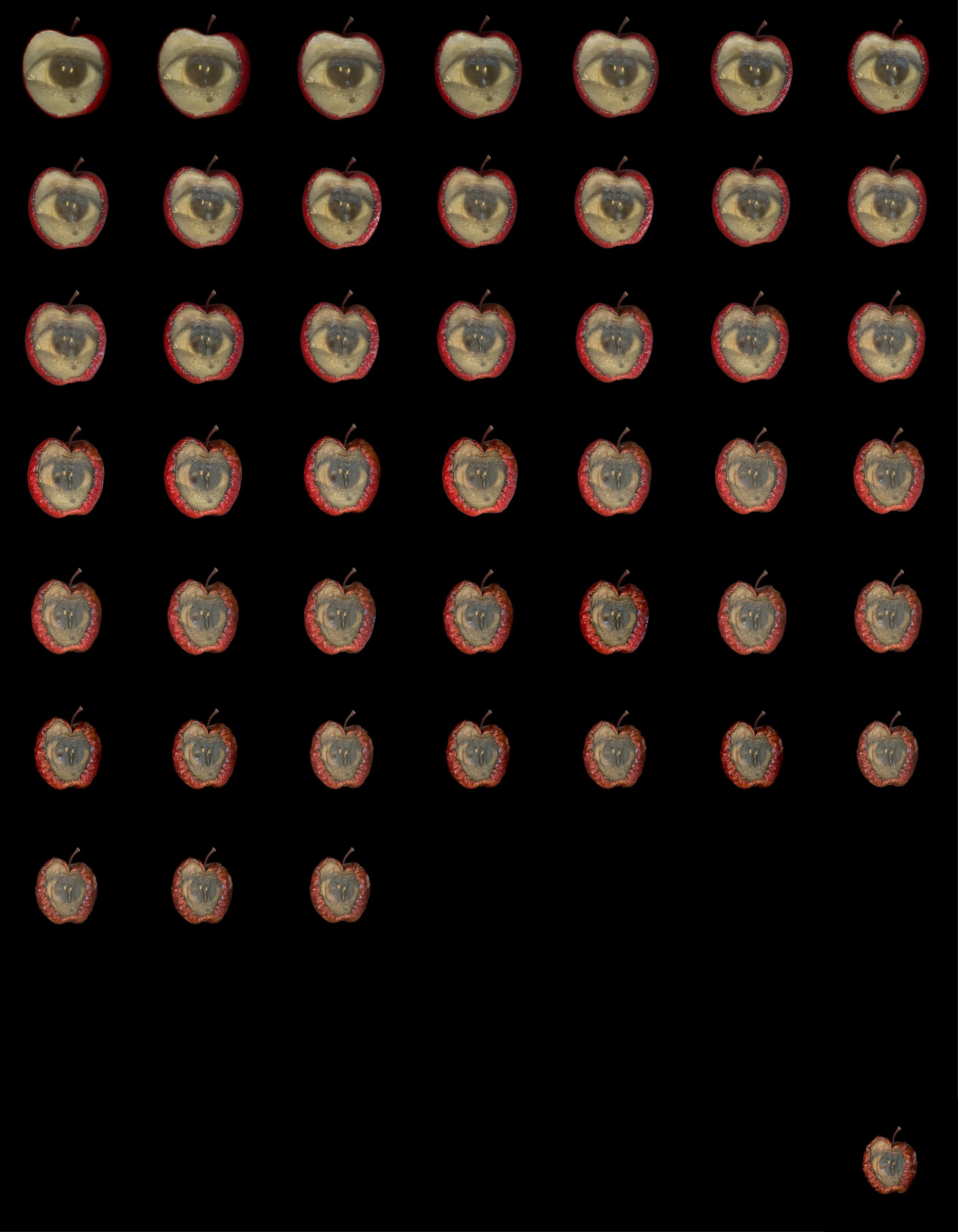

Q5: In your work Apple, it seems you’ve extracted and magnified certain moments from a continuous flow of time. Could you tell us more about the background and process behind this piece? How long did the entire creation take?

Zhang Kailai: For me, taking photos is a way of spending time with time—it’s a bit like trying to leave a mark on it. So in that sense, it feels quite natural that “time” has become one of the central themes in my work.

Apple is part of a series I created using a Polaroid Macro camera. In 2019, Polaroid announced via social media that it would stop producing wide-format film compatible with this camera. Then, on January 1, 2020, I discovered that the camera hadn’t made it into the new decade with us—its digital clock had automatically reset to 1994, the year it was born. This seemed to imply that its designers had never expected it to live this long.

Although I stockpiled a large amount of film in an attempt to prolong its life, the camera still seemed destined to leave us. After years past expiration, the film began failing to produce complete images or accurate colors; the results grew increasingly blurred. That’s when I started using it to capture fleeting moments of life.

In this series, aside from apples, I also photographed many other plants—documenting their full life cycle, including withering and decay. Due to the particular properties of Polaroid materials, it’s possible to transfer the emulsion so that the image physically adheres to an object. These still images could then cling to living matter like a second skin.

In Apple, I documented the changes in this composite life form on a daily basis. Each of these frozen moments is, in itself, a slice of time. In film, freeze frames are often used to let the audience focus intently on specific details within the image. I, too, was trying to use brief stillness to help viewers feel a single moment within the flow of time.

My Polaroid Macro series is a long-term project that began in 2020 and continues to this day. If we count only the time it took to complete the final version of the Apple series, it was around two months. But the process also included many rounds of experimentation and failures caused by unpredictable factors—such as the apples becoming moldy or spoiled due to the humid climate. If we include the entire period of exploration from start to finish, the project likely took about a year.

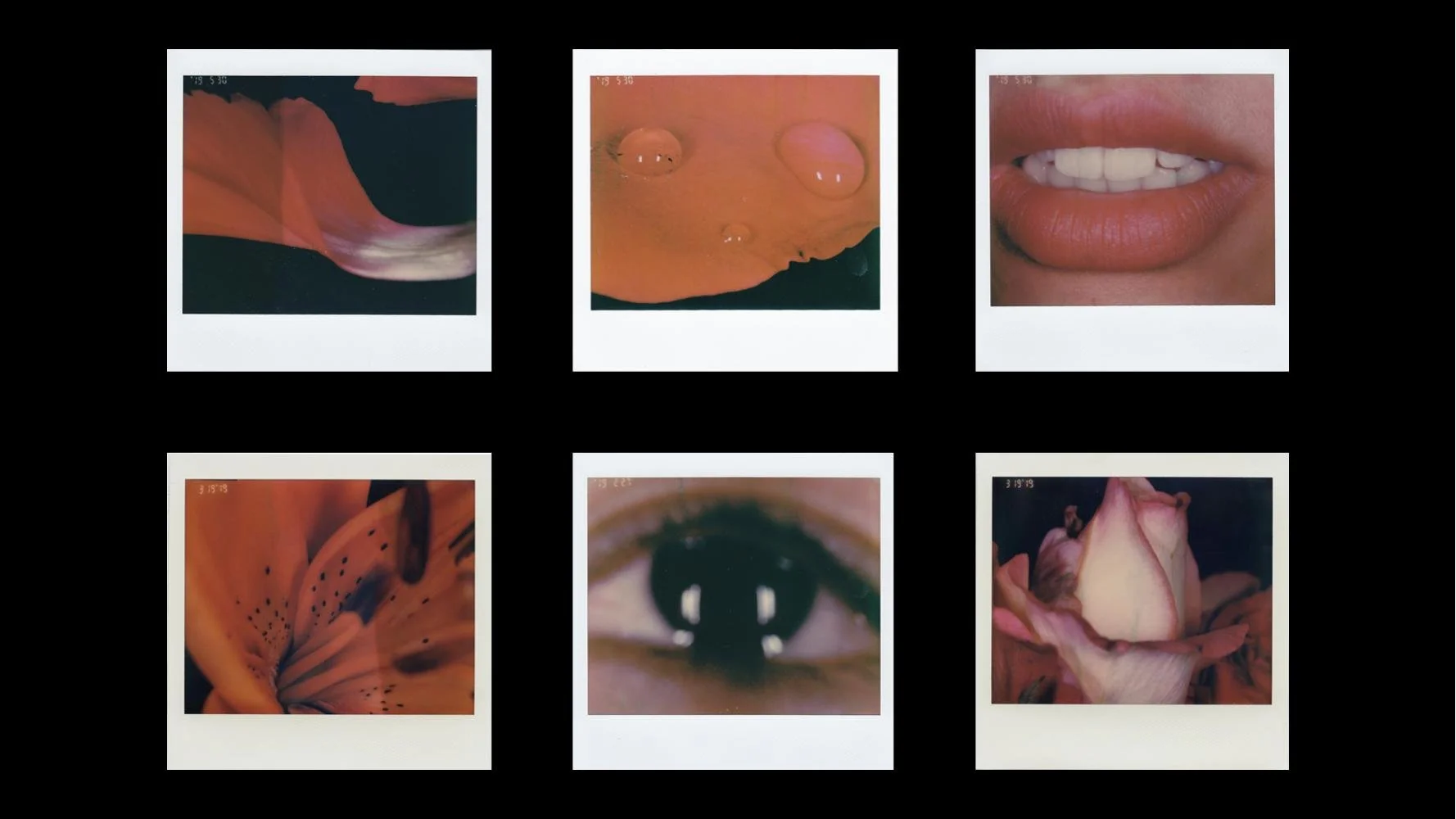

Painful Pleasure,2020

Q6: Is there a particular meaning behind choosing to “transplant” an eye onto the apple? The eye, as a specific image, creates a curious sensation of mutual gaze between viewer and artwork—it may even suggest that, even as observers of the apple, we ourselves are always being watched by time. As the creator, do you feel this too? (And if so, does that bring a sense of certainty in writing your life story at your own pace, or a deep awareness of being trapped in an inescapable framework?)

Zhang Kailai: Your interpretation reminds me of Nietzsche’s concept of “eternal recurrence.” He suggested that the experiences of life will repeat endlessly—what we go through now, we’ll go through again in the near future, like a loop with no end. When I first encountered this idea as a child, it felt a bit abstract, but over time, my understanding of time has grown closer to it.

“Recurrence” is a kind of circular time. In religion, the cycle from birth to death—what’s considered a “complete journey”—uses life itself as the unit to measure time. But the time we experience in everyday life also loops endlessly. For example, in psychology, there’s a notion that unresolved life issues tend to repeat. I suspect that time may operate in a similar way—it might have a spiral structure (though I realize this is still using spatial logic to describe time), or it may be something more multidimensional, like parallel spaces.

Whether we accept it or not, the experiences brought by time will unfold regardless—and they will return again in the next “cycle.” Even if nothing can be changed, perhaps we can try to leave a mark within time, so that when we pass through again, those traces will still be there.

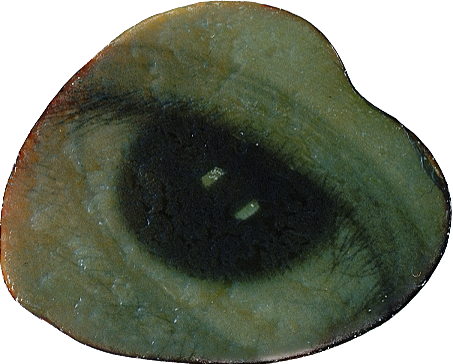

苹果,2021

I’ve done other works involving apples in the past. I’ve always had a fondness for foods that are round in shape and warm in color. Apples were the most common fruit in my hometown, so I’ve been familiar with them since childhood. They’re gentle, non-aggressive, tasty, and offer plenty of creative possibilities in cooking—perhaps that’s why they keep appearing in my work.

In art history, in historical contexts, even in religion, apples have been imbued with a wide range of meanings across cultures. In many mythologies, they are associated with love and life. In Apple, the apple itself—botanically speaking—is a plant’s reproductive organ, while the eye is a human sensory organ. From a biological perspective, they are “equal” as organs. The “transplant” creates a composite life form, one that is constantly restricted, shaped, and altered through mutual interaction.

As the apple is transformed by time, the image of the eye also undergoes a process of abstraction and blurring—as if vision itself were gradually fading under the influence of time, slowly dissolving alongside the changes of life and time. Time exerts its force equally, inexorably, on all forms of life—eroding, transforming, and carrying everything, like a river, further and further downstream.

Monologue,2019-2020

Q7: Polaroid has long been your primary medium—many of your works since you began photographing have been closely tied to it, including 苹果. What draws you to Polaroid? And how has this preference shaped your way of observing or seeing?

Zhang Kailai: What I love about Polaroid is its immediacy and its strong sense of the moment. When shooting isn’t cost-free (as it is with digital), and when there’s no way to edit afterward, it forces you to think more before pressing the shutter. It also makes you pay more attention to what you actually produce.

When photography was first invented—the earliest photographs—it was a record of duration. But as exposure times shortened, it gradually evolved into a medium for capturing “moments.” So photography as a medium has always had a deeply embedded relationship with the concept of time.

Polaroid comes very close to how I understand photography: as a way of marking time. It gives form to something as abstract and intangible as time, to a certain extent. Even though it might be a futile attempt—because time doesn’t actually stay just because we’ve taken a photo—the physical photograph might still spark the illusion or hallucination in the photographer that something has been preserved.

Monologue,2019-2020

Q8: Is there anything you can share with us about your upcoming projects?

Zhang Kailai: Lately I’ve been organizing my previous works—I really want to make a photo book, so I’m currently trying to sort through and curate my images.