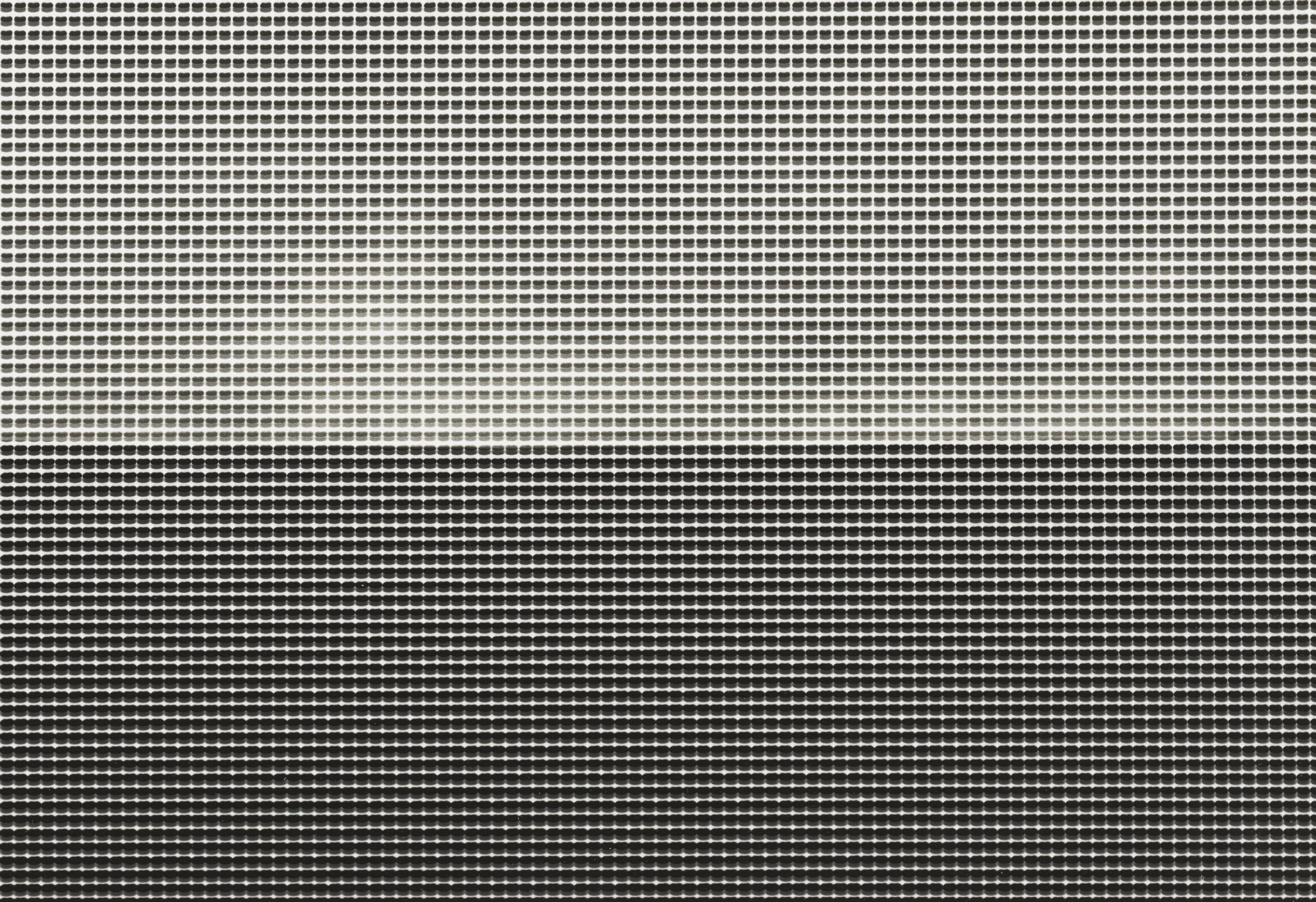

Form and Emptiness - time, 2019

Interview | What Time Is It Now:

Wei Wentao

17/05/2025

This June, MoMingTang will present the exhibition What Time Is It Now at its London space. Showcasing video works by four artists—Zhang Kailai, Wang Xuehan, Wei Wentao, and Shi Hui—the exhibition seeks to explore the possible alternative forms of time, a concept that is vast, ancient, and yet deeply intertwined with our daily lives.

In the works of these four artists, time is no longer a linear thread. It is sliced, collaged, compressed, and then unfolded. Throughout this process, we witness how corresponding narratives shift and how the so-called reality begins to loosen. To imagine “other forms” of time is also to imagine “other ways” of living. In this sense, the exhibition attempts to ask: If time is not linear, how might we reinterpret the events in our lives? If the concepts of “past” and “future” are not as solid as we take them to be, how might our emotions shift—and how else might we live?

This series of posts will present our interviews with the four participating artists. Each of them, in their own way, disturbs reality. In our conversations, they shared how these disturbances come to be.

Wei Wentao

Is a visual artist and photographer. He graduated from the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York and the University of Glasgow in the UK. His work has been recognized with several awards, including the Kunpeng Award from the 2022 China Youth Photography Promotion Project at the Pingyao International Photography Festival, the PDN Curator Award 2018, the IPA Photography Awards 2018, and the PDN Photo Annual 2017. His work has been exhibited in China, the United States, the United Kingdom, and other countries. He has previously worked at Yossi Milo Gallery in New York, the studio of artist Adam Fuss. He currently lives and works in Beijing. His practice primarily explores the impact and reshaping of humanity by contemporary technology through photography and other media.

Q1: What time is it now?

Wei Wentao: Just take a look at your phone and you’ll know.

Q2: In everyday life, are you someone who often pays attention to time? Do you tend to see time as an effective measure created by humans to align and synchronize with one another, or as a trap of collective self-discipline?

魏文涛: I suppose I’m someone who pays quite a bit of attention to time. I think both the measuring tool and the trap coexist by nature—it’s just a matter of perspective. From a macro point of view, humanity laid the foundation for the agricultural revolution by observing astronomy and revising calendars. From knot-tying records to the invention of clocks, increasingly precise measurements of time have driven the development of science and civilization, while also slicing up each person’s day with ever-greater precision.

From a micro perspective, time is actually highly subjective. At different stages in life, each person experiences and perceives time differently—some dwell in the past, some live in the present, and some look toward the future. These varying perceptions of time directly or indirectly influence every decision we make in life.

Q3: Could you talk about how, in your view, social media has changed our perception of time—especially the “present moment”—in relation to your work Form and Emptiness - Time?

Wei Wentao: On one hand, social media has psychologically accelerated our perception of time. The smooth surface of a phone screen eliminates the real distance between people and objects, thereby dissolving any sense of opposition to reality. With just a flick of a finger, the digital world obediently scrolls before our eyes. Immersed in a flood of tailor-made information, people quickly lose themselves in it, which compresses long periods of time into what feels like a brief moment.

On the other hand, social media can also stretch our perception of time. When we view others’ posts and updates, we unconsciously project ourselves into their lives, creating the illusion of living across multiple timelines simultaneously.

The work Time is a 24-hour exposure of the clock display on a phone screen. In doing so, it captures all the time of a single day in the digital world, freezing it into a single image. Through this, I wanted to present a non-linear state of time within the digital realm—where the past, present, and future coexist—thus challenging our ingrained understanding of linear time.

Q4: In several photographs from the Form and Emptiness series that strongly relate to social media, you use varying exposure times to simulate the persistence and fading of memory, resulting in significant loss of visual information. What is it that you hope to preserve through these images? Do you believe photography can be a medium to help us resist forgetting?

Wei Wentao: First, allow me to describe the process behind these works. In the darkroom, I used two phones—one I held in my hand, browsing social media as I normally would, while the other was placed under an enlarger, mirroring my actions. This entire process was recorded directly onto silver gelatin paper. Through this method, I wanted to present the essence of the digital world, reducing information back to pixels—“0”s and “1”s. If the screen is the infrastructure of the digital world, then what I tried to capture was the very state of being as information passes through it. It reveals a kind of void—how human memory becomes fragmented and eroded under the constant wash of information overload.

As Roland Barthes suggested in his idea that “photographs attest to what once existed,” photography can help us remember a person or a thing, and can trigger memories when we revisit the image at some future point. But it cannot reproduce the memory formed in the brain by the direct experience of the moment itself. Contemporary people are often too eager to digitize the world through their phone cameras, placing the device between themselves and reality. They substitute the phone for their own senses, and the act of taking photos replaces direct experience—resulting in a diminished sense of personal participation. So, paradoxically, photography may in fact make us more prone to forgetting.

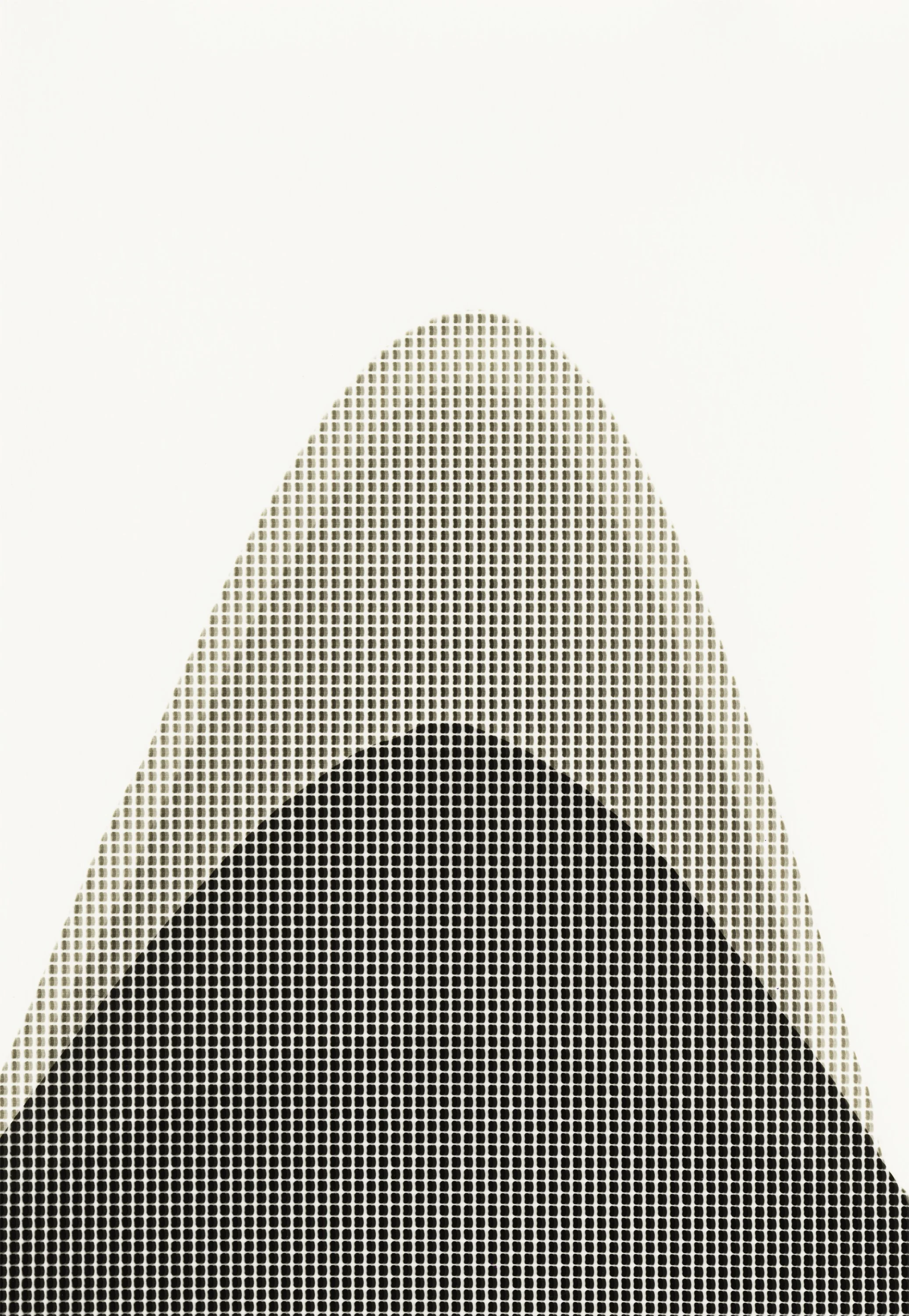

Q5: This series also includes other works that symbolically reference the basic natural elements of wind, water, earth, and fire. Are there any differences in creative approach compared to the social media-related pieces? Could you walk us through the specific process?

Wei Wentao: The starting point of this project was my desire to bring the information that exists on phone screens into the real world through an analog method—that is, to transform two-dimensional images into three-dimensional physical objects. I began thinking: what would the digital world, if expanded into three-dimensional space, actually look like? That led me to recall the ideas of some early Greek naturalist philosophers, who believed the world was composed of four fundamental elements: wind, water, earth, and fire. So I took those elements as the starting point for this part of the work.

These pieces differ from the later social media-related works. The process mainly involved directly exposing pixels onto silver gelatin paper, and then using the chemigram darkroom technique—applying developer and fixer as if they were pigments—to “paint” more abstract forms, much like making a painting.

Q6: You mentioned that the initial intention behind Form and Emptiness was to “bring what exists on the phone into the real world.” The series, through the materiality of the image, builds a channel between the digital and physical worlds. Is construction a central concern in your photographic practice? Why is physical materiality important to you?

Wei Wentao: When I first started creating, construction wasn’t really my goal—it was more of a result that naturally emerged from the process. I think it may stem from a kind of nostalgia I have for objects. As I mentioned earlier, nowadays phones are increasingly replacing our sensory systems, and also replacing many objects in our lives that once brought us beautiful memories—things you could hold in your hand, feel the texture of, appreciate the design of, give as gifts, or collect as vessels of a particular era’s culture.

By digitizing everything in the world and reducing it to information, the phone strips the world of its physical reality. Yet few people attempt to reverse that flow—to turn digital information back into tangible material in the real world. I suppose that’s exactly what I want to do.

Form and Emptiness:

Q7: In the process of constructing the digital world through photography, you initially chose to intervene manually, but later abandoned such subjective interference. Was this a move toward aligning more closely with the natural formation of the real world? Is it a reflection on human desire for control?

Wei Wentao: Yes, I hoped that the digital world could reveal its own existence in its own way, so I reduced the additional attributes I was imposing on it. It’s a bit like how AI, though created by human code, has sparked concerns in academia that it may develop its own consciousness and become uncontrollable after reaching the singularity. Because its way of thinking is different, only silicon-based life can truly express itself.

As for my own creative process, it wasn’t so much a reflection on humanity’s desire for control—rather, the adjustments I made were simply based on methodological considerations and how the project developed over time.

Q8: Will your future creative direction continue to focus on modern technology and information?

Wei Wentao: My recent works have also followed this thread of exploring the relationship between humans and modern technology. For example, during my residency in Suzhou last year, I created two new installations: 黑盒傀儡 and 黑镜子. The former consists of seven black acrylic panels shaped like smartphones, each displaying screenshots of apps I frequently use (Red Note, bilibili, QQ Music, Meituan, Taobao, Xianyu). These screenshots reflect my personal preferences as shaped by big data algorithms. Alongside them, I exhibited the outfit I wore on the first day of the residency, suspended in the space—together they present a near-transparent portrait of myself to the viewer, containing metaphors for information cocoons and algorithmic surveillance.

The latter work uses 100 black acrylic “phones” to display 100 different emojis, pointing to how, in the digital age, people are more easily lost in a world constructed around the self. This narcissistic, even isolating tendency has led to an increasing neglect of others, and a deepening sense of loneliness among individuals today.

In the future, I still hope to use art to explore the friction between humans and technology. I may move beyond photography and two-dimensional works, and create more spatially immersive installations.

Site photos of the residency project

像素RGB,2024

《黑镜子》,2024

《黑盒傀儡》,2024

《拥抱》作品局部

《拥抱》,2024