Interview | What Time Is It Now:

Wang Xuehan

27/05/2025

This June, Momingtang will present the exhibition What Time Is It Now at its London space. Featuring moving image works by four artists—Zhang Kailai, Wang Xuehan, Wei Wentao, and Shi Hui—the exhibition seeks to explore the possible alternative forms of time, a concept that is vast, ancient, and yet intimately tied to our everyday lives.

In these artists’ works, time is no longer a linear thread. It is sliced, collaged, compressed, and then unfolded. Through this process, we witness how narratives shift and how so-called reality begins to loosen. To imagine other forms of time is also to imagine other ways of living. In this sense, the exhibition asks: If time is not linear, how might we reinterpret the events in our lives? If concepts such as “past” and “future” are not as fixed as we tend to believe, how might our emotions shift—and how else might we live?

This series of features will present our interviews with the four participating artists. Each of them, in their own way, disrupts reality. In our conversations, they share how those disruptions take place.

Wang Xuehan

Born in 1994 in Changde, Hunan, he primarily works with photography and video installation. Influenced by Eastern traditional culture, his practice often begins with questions and explores the underlying mechanisms of the world from an experimental perspective. He focuses on the expressive possibilities of images across different media, seeking to make art a vessel for thought and experimentation.

Q1: What time is it now?

Wang Xuehan: I don’t know. I usually live according to my sense of time rather than the clock—unless I’ve made a plan to meet someone at a specific hour, I rarely check the actual time. For me, the day can more or less be divided like this: I’ve woken up; I’m hungry; I’m sleepy; I feel like going for a walk; I’m too tired to stay up and need to go to bed. Right now, I’ve just finished brunch and I’m at that slightly drowsy part of the day.

Q2: You’ve given yourself the nickname “Wang Midnight.” Why have you become such a nocturnal creature?

Wang Xuehan: I sleep a lot during the day, so of course I’m full of energy at night.

Q3: From the perspective of your practice in Chinese metaphysics, are the past, present, and future clearly separated? How do you understand time?

Wang Xuehan: If I look at things from the perspective of a metaphysics practitioner, the dimension of time can sometimes interfere with my understanding of the nature of things. For example, an apple seed inherently carries the properties of an apple—that’s a kind of stability encoded in its DNA. Normally, when we talk about an apple, we strip away the time dimension and focus on its intrinsic characteristics.But once we add time into the equation, that apple seed may go through a natural cycle of growth, flourishing, and decline. And that cycle can vary across time and space—it might wither due to a natural disaster, or differences in climate between the north and south might influence the fruit’s size and taste. Still, one thing remains constant: if that seed bears fruit, it will be apples.

In my view, there are no sharply defined boundaries between past, present, and future—they all belong to the same dimension of time. What interests me more is: what remains outside of that dimension? People often talk about the possibility of other choices unfolding in parallel timelines. But if you remove the time dimension altogether, there are actually no “other” choices for a single entity—because I am who I am.Even though external conditions may be unstable or unpredictable, the essential traits of an individual remain relatively constant. So even if “I” make different choices in different circumstances, and those lead to different outcomes, there is still only one essential “me.” What I care about is that relatively stable self, once time is taken out of the picture.

I’ve always been fascinated by the ideas of change and constancy—what tends to shift, and what tends to stay the same. I think everything operates according to that logic. In real life, though, it’s hard to observe something purely unchanging or purely changing. More often, we see them progressing simultaneously, and it’s from that interaction that we derive meaning or conclusions. In my own work, I’m always searching for what changes and what doesn’t. But I don’t think one is better than the other—they’re both important. Because only when change and constancy form a kind of spiral dynamic can things move forward and the world continue to operate with stability. I believe human civilization evolves through this very structure.To give an example from my own practice: mountains appear often in my work. I sometimes imagine a small village at the foot of a mountain—villagers living through generations of birth, aging, illness, and death, while the mountain remains relatively unchanged. Its presence and its impact are relatively stable.What interests me is the relationship between cultural shifts in human society and the relatively constant natural environment. Put simply, I’m drawn to the tension between things that stay the same and people who don’t.

Q4: In terms of your creative philosophy, you seem to trust and even require the presence of “rules”—within which you then explore as freely as possible, almost playfully. Why, in your view, are rules a prerequisite for freedom?

Wang Xuehan: I think you have to first recognize the existence of rules before you can even begin to understand freedom. Freedom can’t exist independently of rules—that’s a cognitive premise.Once you identify the rules, you can define the boundaries. Only by subtracting that known, defined space from the unknown can you locate the areas of freedom—both within and beyond the boundaries. It’s a way of identifying limits: I need to first recognize what is recognizable before I can understand where the unrecognizable begins.So I think, the more clearly you can map out the edges of the rules, the more freedom you gain—because the more precisely you understand the limits, the more you know where you’re free to move. I see rules and freedom as relative to one another: the greater the freedom, the more rigorously it is framed by some kind of structure. In a way, the freest states are also the most disciplined.

Q5: You’ve said that games provide a context in which the self (or behavior) can be magnified or extended—and that this corresponds perfectly to the nature of Chinese metaphysics, which reveals the greater through the smaller. Is that why you’re so drawn to metaphysics and have brought it into your artistic practice?

Wang Xuehan: It’s not that I deliberately brought metaphysics into my art—there isn’t a causal relationship like that. Although, chronologically speaking, I did start making art before I began studying metaphysics, I never initially intended to incorporate it into my creative work. What actually happened was that, during my study of metaphysics, my way of thinking and perception began to shift—and that shift sparked a strong urge to create. For me, the transformation of cognition was more important than metaphysics itself. Metaphysics was the ladder that helped me reach the second floor; it’s a tool, a method. But reaching the second floor was the actual goal. Even now, I remain hesitant and cautious about directly presenting metaphysics in my work. I don’t want people’s attention to fixate on metaphysics and overlook everything else. Because once you’re on the second floor, you’re supposed to gradually forget about the ladder. That’s why, to this day, Fate Diagram (命运图例) is really the only work of mine in which you can clearly see a direct connection to metaphysics.

When a person writes or takes photographs, they’re ultimately expressing what they perceive and what they think. Since metaphysics has given me a new way of thinking and perceiving, it inevitably influences my artistic practice. In fact, metaphysics has fundamentally changed the way I understand the world (as reflected in my view of time in the first question)—its impact goes far beyond art alone. For me, metaphysics and art-making are like the two pedals of a bicycle. When I press down on the left pedal, the right pedal naturally comes up; when I press the right, it lifts the left again. They exist in a cyclical relationship, continuously propelling each other forward. Metaphysics brings about a shift in cognition, which in turn gives me something I want to express—it drives my artistic creation. But artistic creation ultimately has to take form in something tangible, like the physical act of pressing the shutter in photography. Whether we treat metaphysics as logic or algorithm, it only exists within the realm of human thought—it has no physical vessel of its own. When I translate the understanding I’ve gained from metaphysics into each photograph I take, into each decision to crop or collage a frame, the physical execution becomes a kind of verification or testing process for those mental insights. Each act of creation is a way of using the material to test the immaterial. And this process of verification continually deepens and evolves my original thinking. Over time, the tangible act of art-making loops back and pushes forward my understanding of metaphysics again. Every time my understanding of metaphysics advances, a new visual approach surfaces in my mind—so I return to the creative process to test it again. In this way, the relationship between metaphysics and art for me really is like the two pedals of a bicycle: each one makes the other move.

Q6: Your creative process often resembles a series of safe yet uncontrolled experiments. Could you talk about how, in your Folded Landscapes series, you use photography to link together multiple independent points in time—and how these scattered temporal slices are reconstructed into a chaotic time-space where you are present?

Wang Xuehan: My current practice revolves around photographic collage. At its core, collage is about the recombination of materials. But for that to happen, those materials first have to be classified according to some underlying structure. In my case, I deconstruct my own photographs into what I consider basic units—elements whose symbolic language feels relatively pure and stable. For example, doors, chairs, bicycles, and beds are among the most frequently recurring elements in my work.

Before I started working with collage, I spent several years immersed in straight photography. At the time, I had a particular habit: I really liked placing a single object right at the center of the frame—often with the object itself lit while the surroundings remained dark, creating an effect similar to stage lighting. I’ve reflected on this visual tendency of mine: am I especially drawn to subjects that possess strong presence or a built-in focus structure? Or is it the atmosphere created by a point-source light that captivates me? (Perhaps it has something to do with my personality—when I look at something, I tend to focus directly and intensely on what I want to see, with a strong sense of purpose and direction in my gaze.) Though I still haven’t fully figured out the reason behind it, those photographs I took back then have provided a large archive of materials for my later collage work. I rarely need to shoot new images specifically for collage experiments anymore.

I enjoy photographing singular subjects. When I’m working with straight photography, there’s usually one object in a scene that powerfully draws my attention—or rather, it becomes the object onto which I project strong emotion. I can almost always remember how I felt and what state I was in when I took each photo. But in the Folded Landscapes series, I deliberately chose compositional strategies that I used to avoid in straight photography—such as removing any single dominant subject from the frame, creating more complex compositions, and even allowing for visual logic and perspective to become unstable or chaotic. In a sense, collage allows me to bring together all the objects that once carried intense emotions, expectations, or symbolic meanings for me. Regardless of whether the final collage has visual coherence or logic, “I” have already emerged in the work.

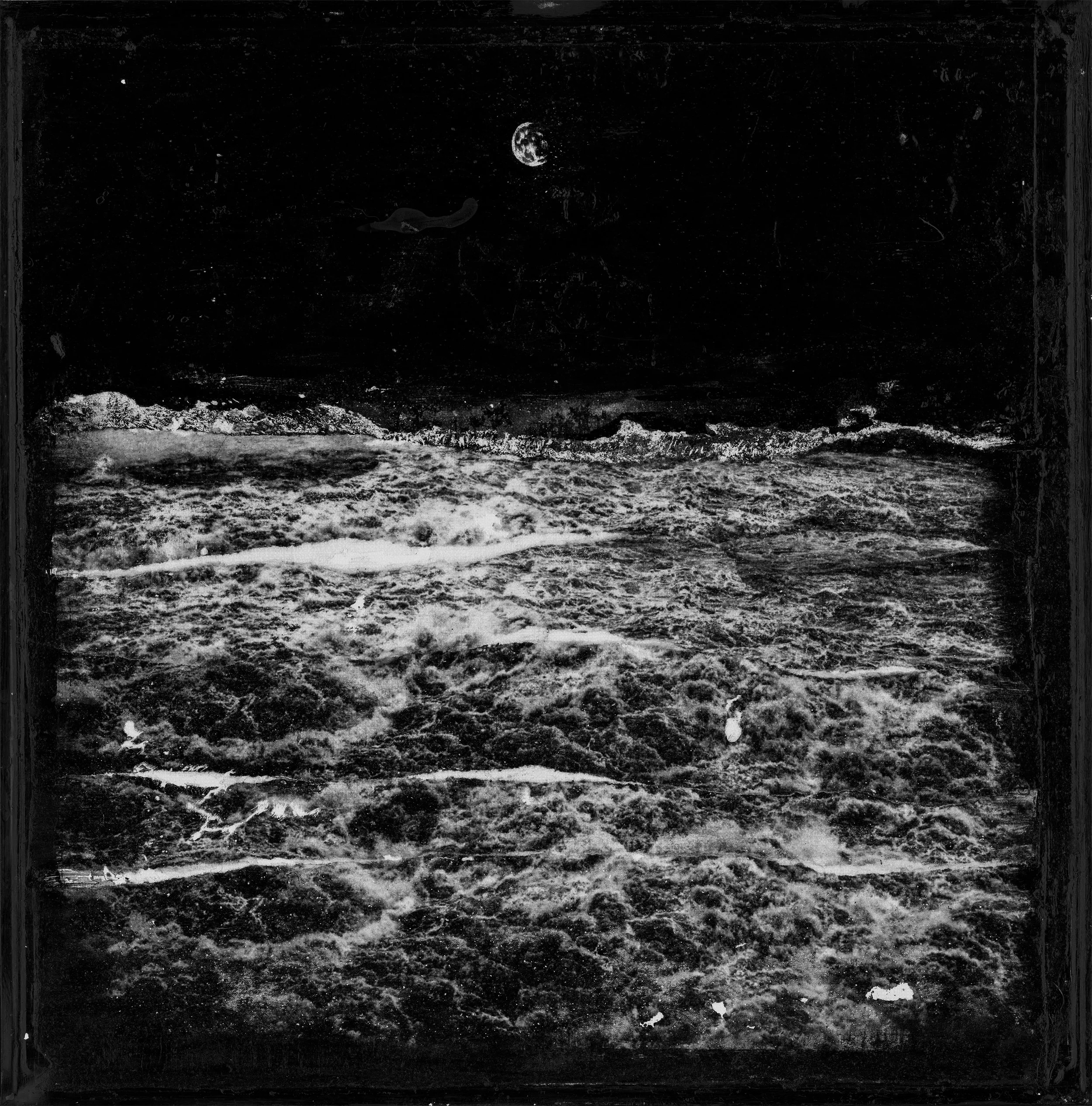

Q7: In Wave Prelude, the visual materials are drawn from both real life and video game environments. In the process of merging these sources, how do you see the materiality of photography playing a role?

Wang Xuehan: I think game photography and photographic collage share something in common—they’re both fictional or virtual in nature. But for me, the materiality of photography is irreplaceable. I often ask myself: collage, in its internal logic, is in many ways closer to painting than to photography. So if I can paint, why not just paint a chair into the picture—instead of going out and photographing one? To me, there’s a profound difference between the two.

The first difference is that, no matter how photography evolves, its visual language always carries a certain sense of truth. Take a chair, for example—even if it’s painted with hyper-realistic detail, as long as it’s a painting, it can never truly convey the feeling of realness. Authenticity is the foundation of photography—and that’s precisely why I insist on using photos I’ve taken myself to construct an image. Even if the final picture is fictional, I believe it needs a real anchor. The truth-value of the photograph is a starting point for my practice. On a personal level, it’s evidence that I have genuinely lived in this contemporary society. I can’t throw that evidence away—because without it, what distinguishes me from someone in the past or someone in the future? And how would my image differ from an ancient painting or a painting of the future?

The second point is that photography, in its current stage of development, gives me a strong sense of unreality. It’s not that the images themselves are unreal, but that the shared consensus around photography today has shifted—it’s become synonymous with digital files. Even though many people still use film cameras, most of them do so just to end up with a digital version—a collection of image files. That’s one of the reasons I quickly lost interest in shooting film. A digital photograph is, at its core, nothing more than code. Once it’s fully reduced to signals made up of 0s and 1s, it becomes too virtual, too elusive for me. I don’t want to do a virtual collage in Photoshop, or on top of a digital image. I need to transform a digital photo into something real—something tactile, something physically perceptible—and then use that material object as the basis for collage. Of course, this process also involves many material considerations. Different materials and their physical properties provide different kinds of creative feedback, each influencing the work in its own way.

Q8: Have you ever used metaphysics to calculate or predict your own artistic path? So far, how closely have the results aligned with reality? (And if there have been periods of significant deviation, how do you view and respond to them?)

Wang Xuehan: That’s an extremely personal question.

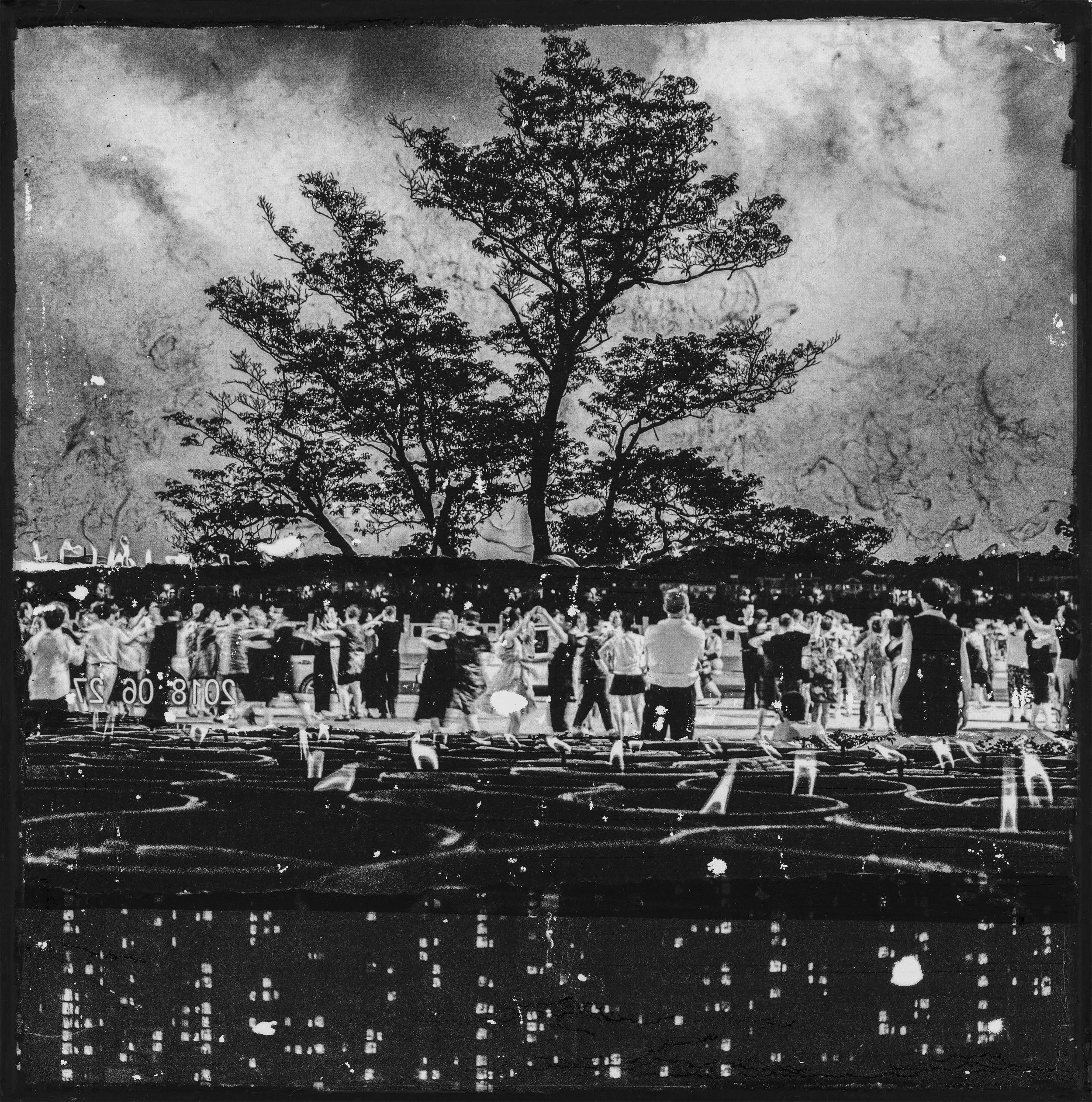

《WASD》:

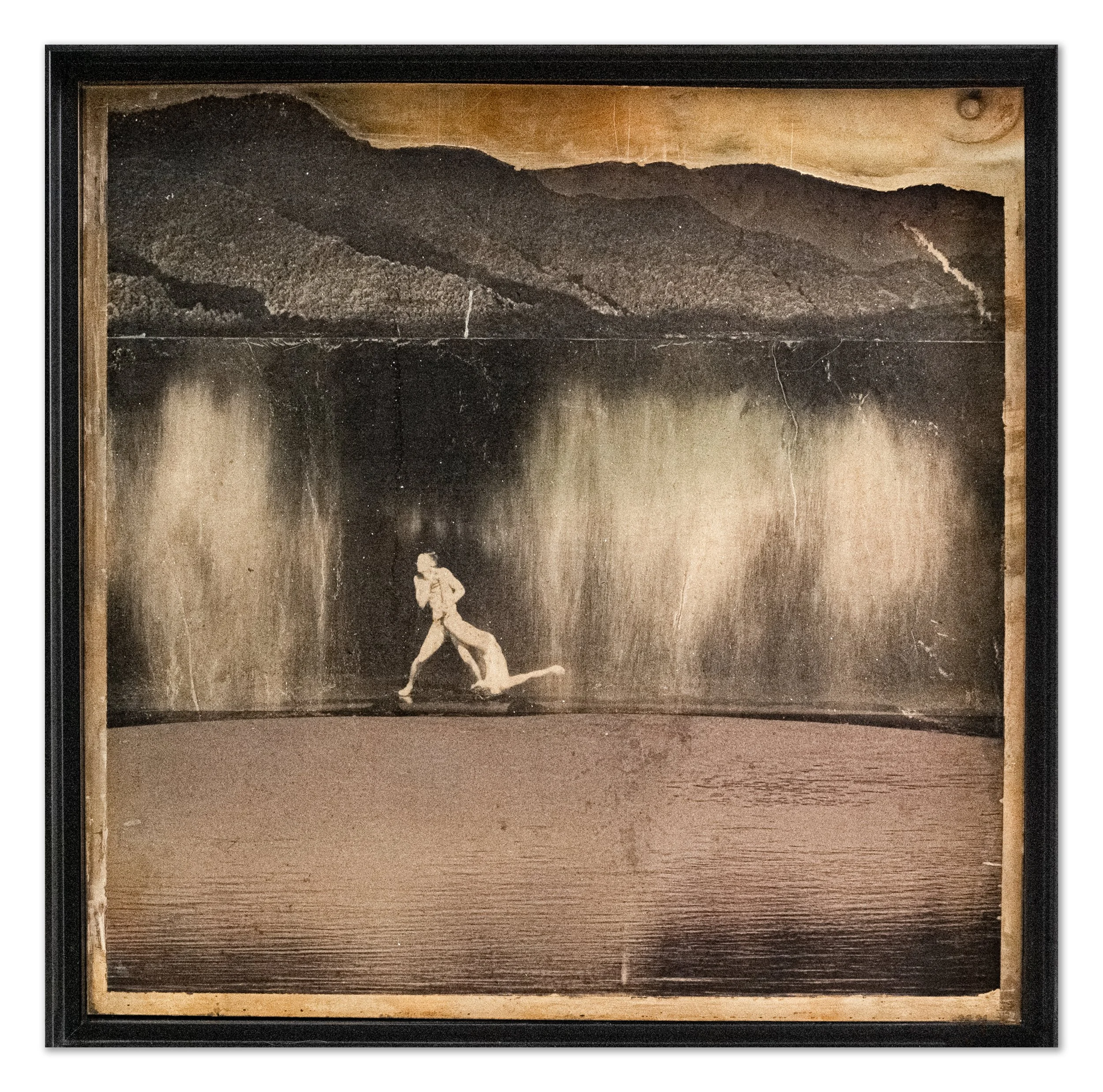

《折叠山水》:

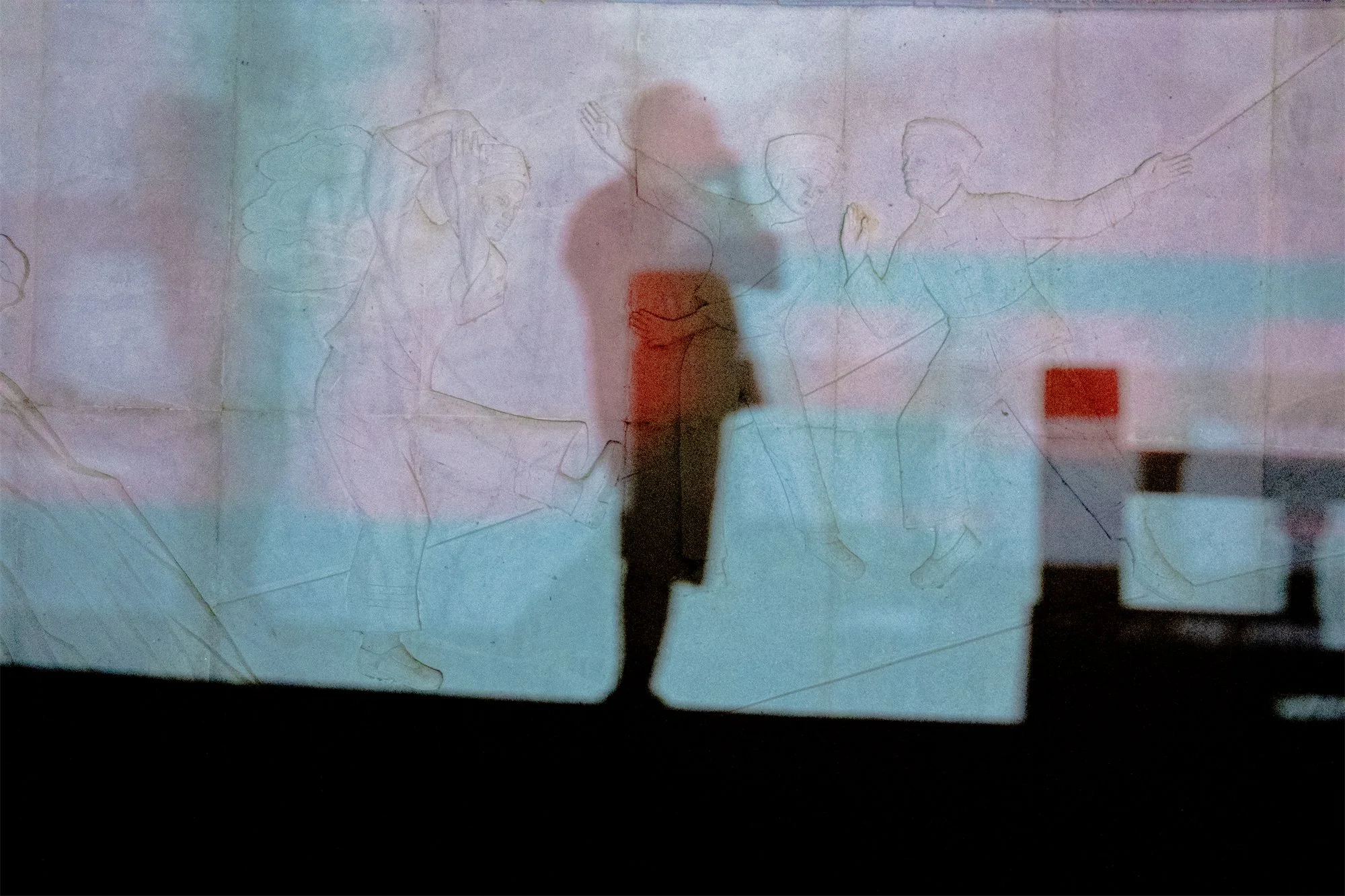

《我见我》:

《海浪序曲》: