《波光》

Interview | What Time Is It Now:

Shi Hui

25/05/2025

This June, Momingtang will present the exhibition What Time Is It Now at London space. Featuring moving image works by four artists—Zhang Kailai, Wang Xuehan, Wei Wentao, and Shi Hui—the exhibition seeks to explore the possible alternative forms of time, a concept that is vast, ancient, and yet intimately tied to our everyday lives.

In these artists’ works, time is no longer a linear thread. It is sliced, collaged, compressed, and then unfolded. Through this process, we witness how narratives shift and how so-called reality begins to loosen. To imagine other forms of time is also to imagine other ways of living. In this sense, the exhibition asks: If time is not linear, how might we reinterpret the events in our lives? If concepts such as “past” and “future” are not as fixed as we tend to believe, how might our emotions shift—and how else might we live?

This series of features will present our interviews with the four participating artists. Each of them, in their own way, disrupts reality. In our conversations, they share how those disruptions take place.

Shi Hui

An independent photographer with a master’s degree from China Academy of Art. Her work focuses on the understanding and exploration of nature, place, and the dimensions of time and space. She currently lives and works in Shanghai and Hangzhou.

Q1: What time is it now?

Shi Hui: 18:04, GMT+8.

Q2: Could you introduce your exhibited work 波光? Under what circumstances did you create it, and what did you want to express through it?

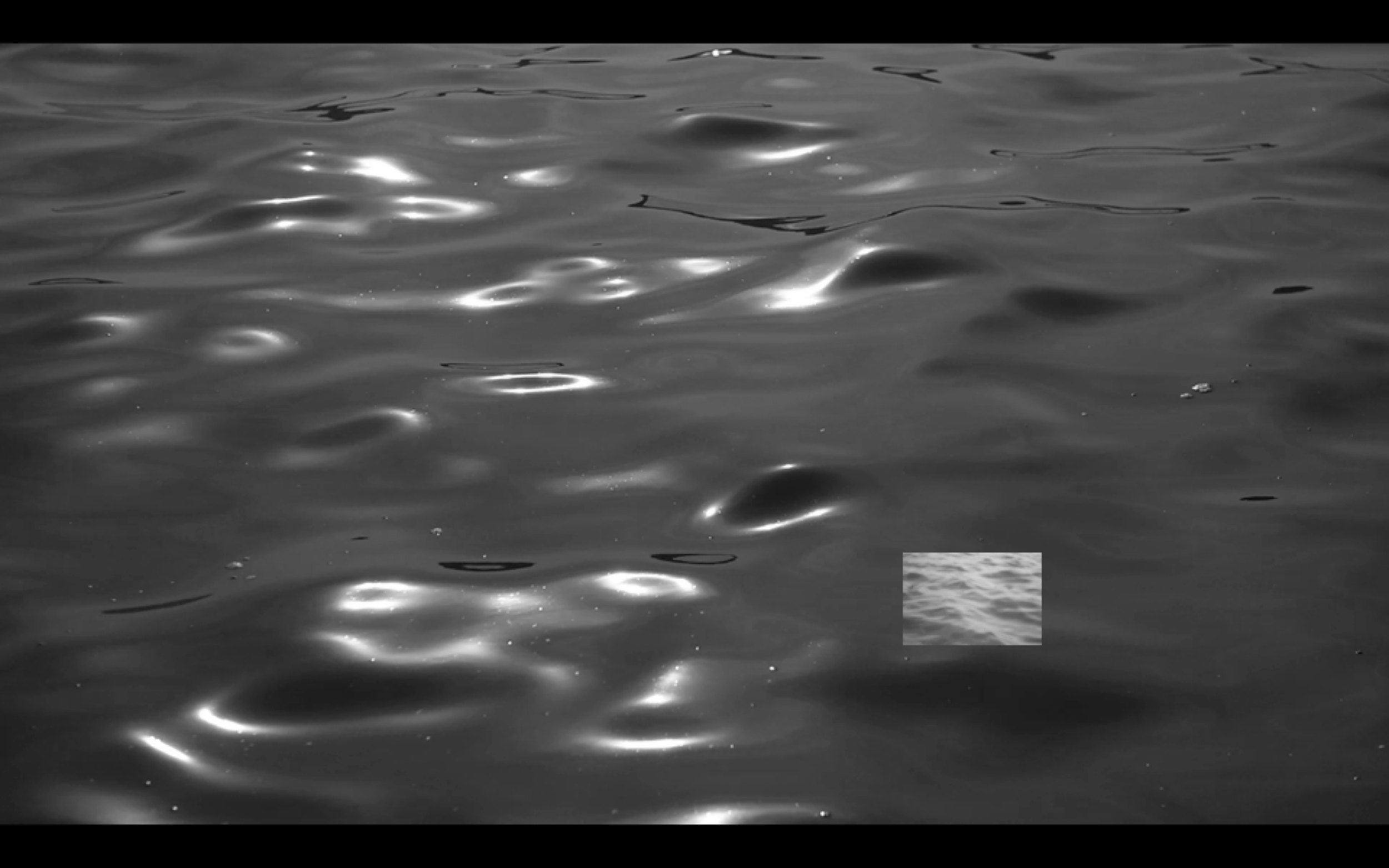

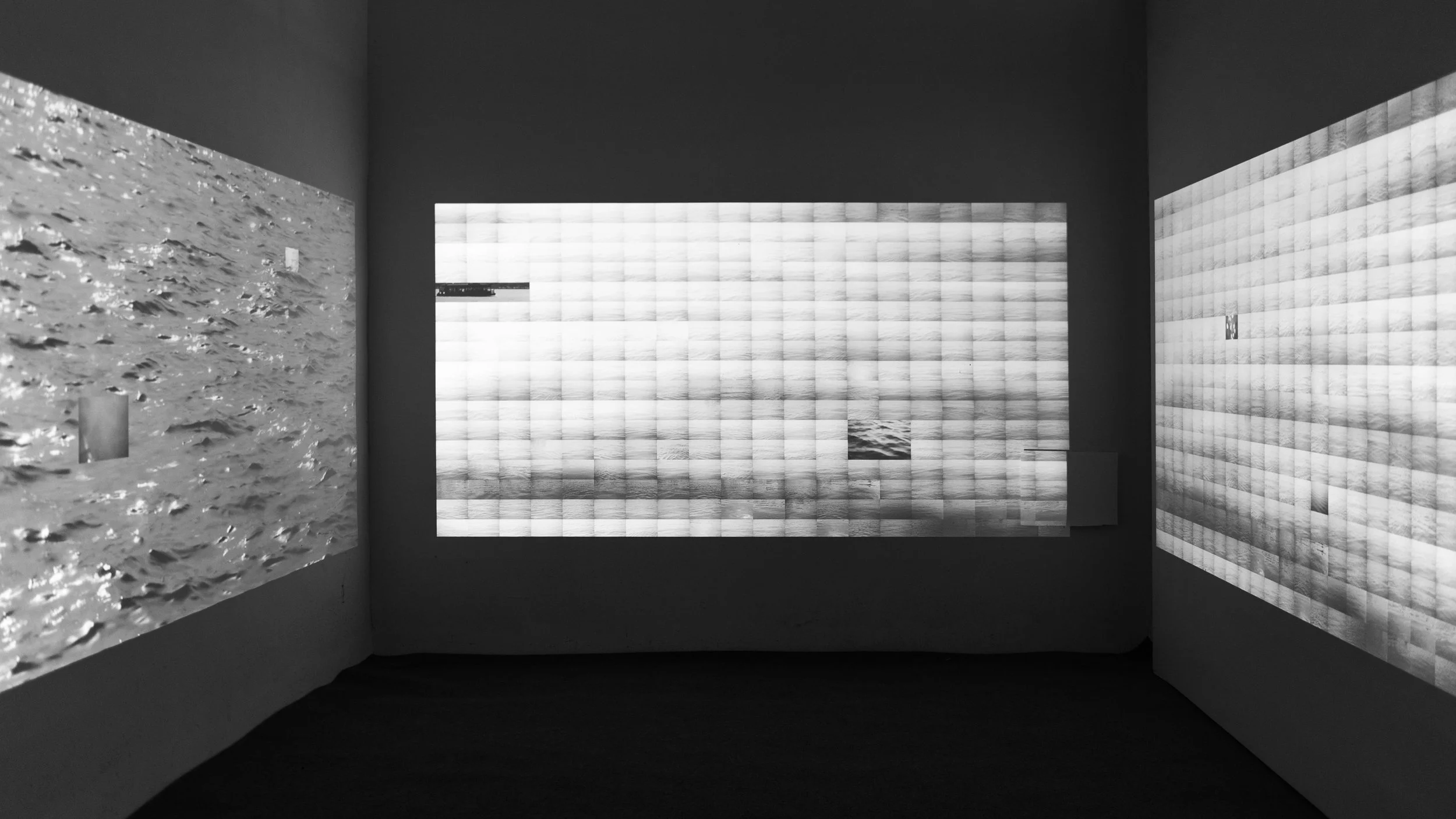

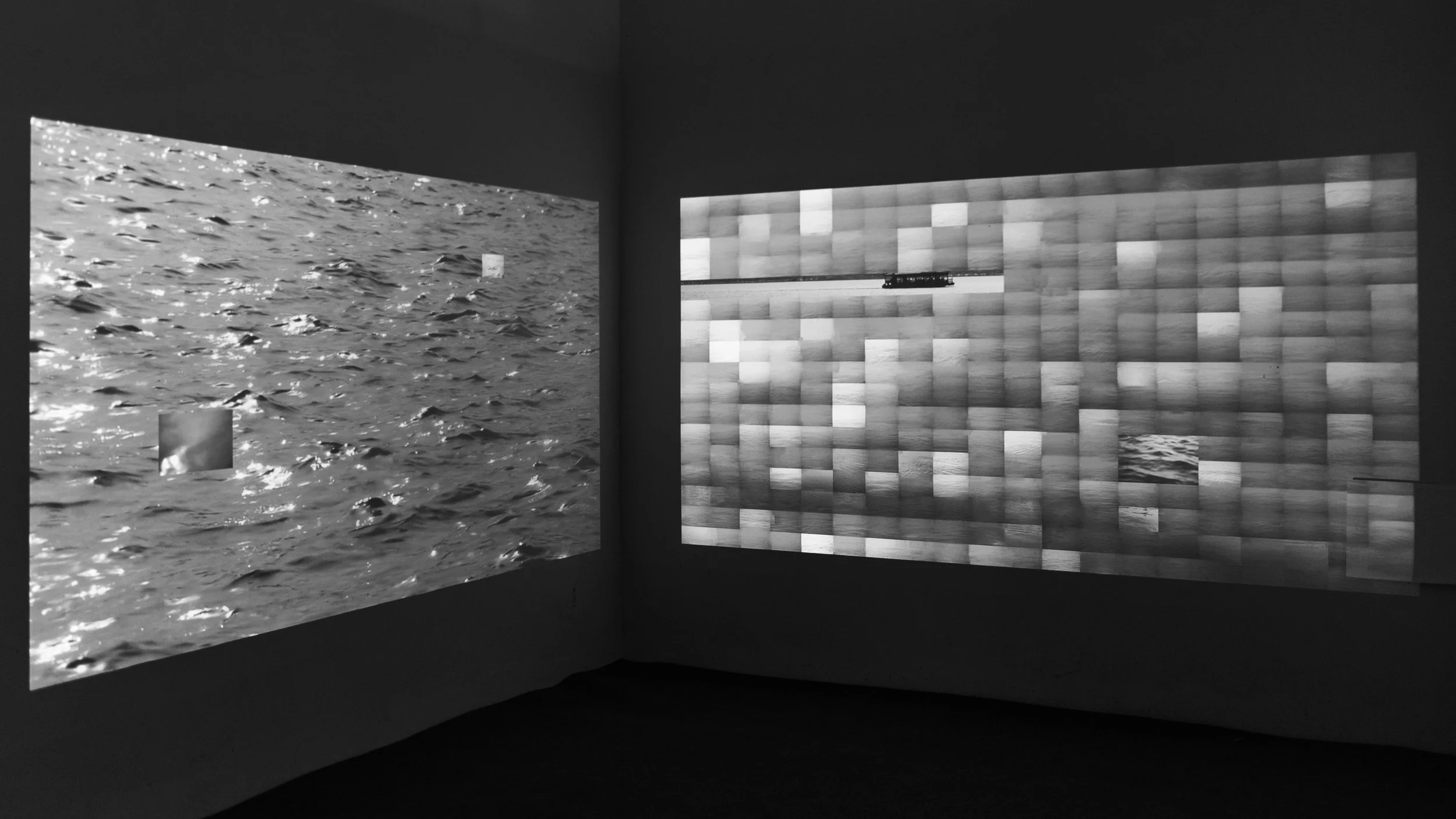

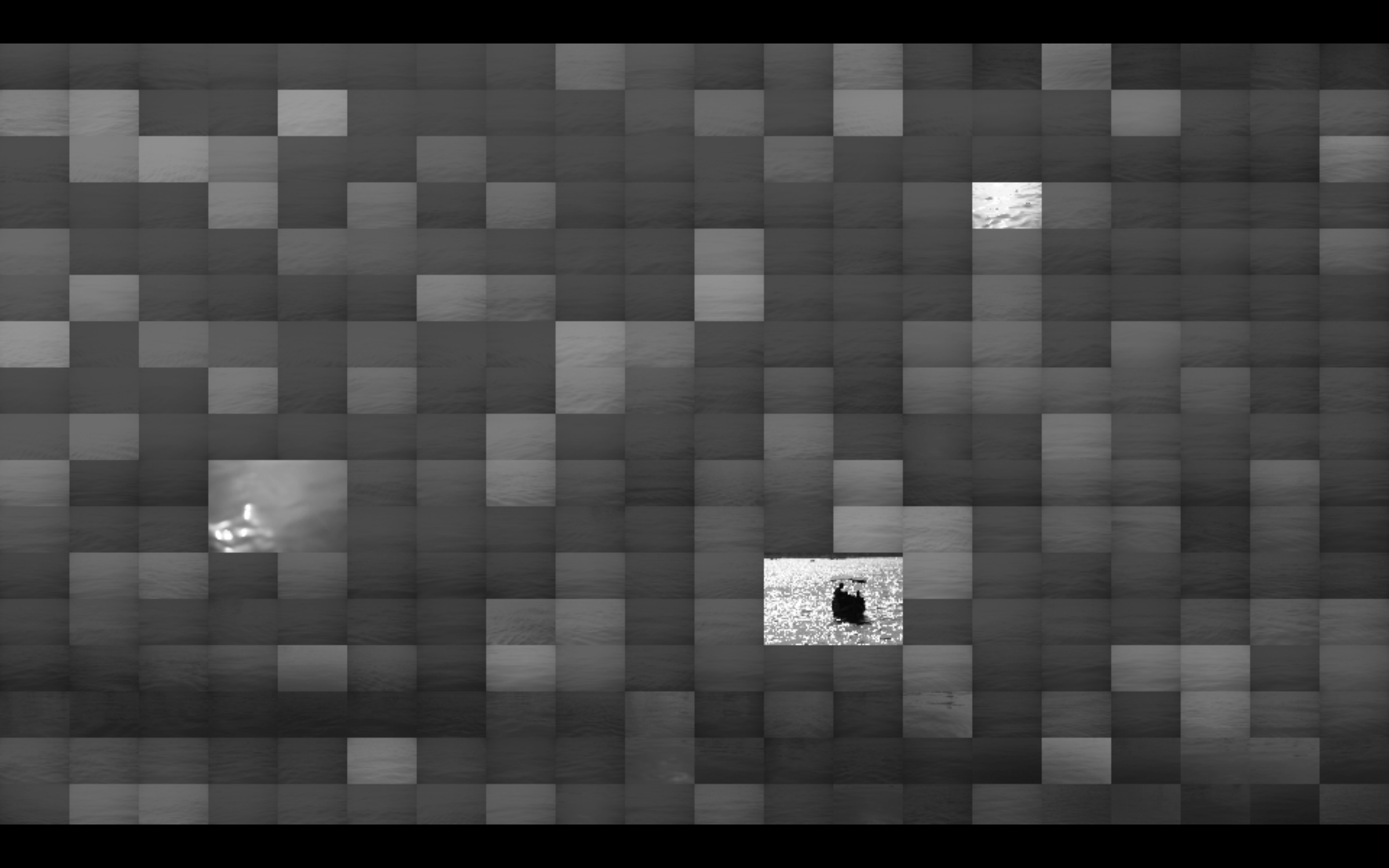

Shi Hui: This piece is a spatial video installation. The video component is a 3-minute sequence in which a boat slowly moves across a water-based image, while additional video fragments are embedded in the textured background. As the sound rises and falls, the light in the image flickers between brightness and dimness. Once the boat passes through, the image eventually returns to stillness.

The work is presented in an enclosed space, where all the light comes from the video itself. When you step into this space, you follow the rhythm of the sound, the shifting light, and the flowing imagery—immersed in a memory of West Lake that I’ve woven together.

The piece expresses how I see West Lake. It is deeply personal and reflects the long-standing relationship between myself and the lake. Whenever I stand at its edge and face the water, the rippling waves feel as though they’re speaking to me—like reuniting with an old “friend” after a long separation. That sense of reunion might also represent a reconnection between myself and nature.

Looking back now, perhaps the desire to leave behind an image of this “friend” had already formed long ago in my mind. All the planning, filming, and production may have simply followed intuition, slowly realizing that idea. So, really, I was just doing something quite ordinary: creating a memento for a friend.

Q3: When I was looking at your new work 古道, I noticed some continuities and shared qualities with 波光, which I found really interesting. In your work, the idea that “photography is a slice” feels particularly pronounced. And I don’t mean just in the conventional sense of photography as a fraction-of-a-second exposure—your “slices” feel more like you’ve taken a real knife and carved out a piece of vision.

In Part Two of 古道, the way the camera follows the gaze and cuts through depth feels like carving ornamental layers through a single hole in wood. And in Part Four, the single photo on semi-transparent material, stacked from a fixed perspective, reminds me of both biological cross-sections and Leandro Erlich’s clouds. Do you feel the same way?**

Shi Hui: I suppose I do! Maybe it’s because when I shoot, I’m genuinely trying to gaze at nature intently—trying to have a conversation with it, haha. If we treat nature as a whole, then just like any living or non-living thing, it can be “sliced” through time into a single moment, or through space into a fragment. Either way helps me better understand and appreciate it.

I really like Leandro’s clouds too. If I remember correctly, he started learning about architecture quite early on, so maybe that’s why he enjoys analyzing something as seemingly irregular as a cloud in such a rational, structured way. Of course, that’s just a little guess from my own perspective.

Q4: There seems to be a consistency between the perspective of your lens, the way your works are presented, and how you position yourself as a viewer within them. In 波光, we see a fixed camera—a surrounding three-screen setup—and a body positioned by the lake. In 古道, it’s more like the hand follows the eye—four chapters unfolding—as one moves through the ancient trail. Is this consistency something you intentionally maintain? Is it planned from the beginning of the creative process, or something that emerges during exhibition?

Shi Hui: That feeling probably comes from the fact that what I’m always trying to recreate is a version of nature marked by my personal imprint. I usually start with a few ideas, but most of the specifics only become clear during the shooting process—through ongoing encounters with nature.

There is one thing that has remained constant from beginning to end: my desire to use the work to restore, as much as I can, what I felt in the actual moment of being present with nature. Maybe it’s this attempt to capture the sense of presence that ends up creating a kind of consistency in the viewing experience.

Q5: Why are you so drawn to using montage or collage?

Shi Hui: It originally stemmed from my research interests. In photography, the forms, concepts, and mediums involved are constantly evolving. A work becomes more like a site where meaning is generated. As a creator, I’m very interested in how meaning is produced within a work.

During this process, I came across some semiotic theories on texts, which describe a text as a kind of fabric—constantly woven and continuously growing. All textual construction is essentially an assemblage of past quotations. Images, as non-verbal signs, are also sites for the production of meaning. So, weaving together different visual materials may manifest in the work as collage, layering, or embedding. It’s a way for me to try to re-create the richness I feel when I’m immersed in nature.

Q6: Whether in 波光 or 古道, there’s a recurring sense of time collapsing across eras—as in the line, “Today’s people do not see the moon of old; yet the same moon once shone on those of the past.” You seem to have a kind of fascination with this type of scene and theme. When did that begin, and why did you choose photography as the medium to explore it?

Shi Hui: I think I’m more deeply drawn to photographing nature or landscapes. Whenever I want to express something through my work, I naturally gravitate toward landscape as the subject. This choice seems to arise spontaneously—it’s hard to trace it back to a specific moment.

Maybe it’s because my focus has always been on the relationship between humans and nature. On the other hand, perhaps it also comes from having lived in highly urbanized environments for so long—when I return to nature, the emotional response is stronger, and I feel a deeper resonance.

As for the sense of scene or thematic atmosphere you mentioned, I haven’t pursued it intentionally, but I really enjoy this feeling of being in dialogue with nature. When nature, from some faraway time and space, presents itself before me, speaking with it might also be a way of speaking with that distant time and space.

Q7: You’ve previously emphasized the importance of nature as both subject and theme in your work. When “nature” and “photography” sit on either side of the word “time,” there’s a certain tension. How do you view the role of time in your work? And what part does photography play within it?

Shi Hui: Nature is far too vast and rich—there’s no way I could ever truly document it, nor could I completely reconstruct it. I think my work is more about capturing how I feel when I’m in nature. By weaving together the materials I gather on-site with my personal experience of being there, I try to reshape a space from different dimensions.

This space, though drawn from reality, is layered with my own feelings and understanding of nature. It becomes an inner landscape—deeply personal and marked by my imprint—so it’s a very subjective form of expression.

When photography is the medium, the temporal aspect of the work becomes unavoidable. And when nature is the subject, that temporality seems to be even more pronounced. The way I record things—fragmented, layered, and reassembled—mirrors how nature itself leaves traces across time and space. It also reflects nature’s richness and complexity as an interconnected whole.

Q8: Are you considering switching mediums?

Shi Hui: I’ve always been thinking about and experimenting with mediums that might better suit my way of expression. In the future, I’ll likely explore a broader range—I don’t plan to limit myself to photography. If I have the energy, I’d love to try out everything that interests me, haha.

But no matter what medium I end up working with, photography will always be the most meaningful to me. It’s been a loyal companion—a kind of bridge that’s allowed me to see more possibilities in myself.