Exhibition:

What Time Is It Now

curators:

Ren Baiyu

Ma Xinyi

Artists:

Shi Hui

Wei Wentao

Wang Xuehan

Zhang Kailai

Exhibition Review|What Time Is It Now

Apple, WeChat, Glisten, and Chaos

The exhibition What Time Is It Now seeks to explore the possible alternative forms that time may take in photography.

A terrible statement—it sounds too grand, too abstract, too disjointed. What does the form of time have to do with me? The answer is precisely this: because it seems irrelevant, we live in a default mode where events occur, then end; we age, and we lose—and that’s it, no negotiation. In this mode, we spend much of our lives living in the past or the future.

Fear is constant, and loss is inevitable. Yet we’ve accepted this way of living—since this is how things are, there is nothing wrong about it—until we see time in other forms and realize that things don’t have to be this way.

Imagining time’s “other forms” is also imagining “other ways of living.” In this sense, the exhibition intends to investigate if time were not linear, if concepts like 4 p.m., Monday, next year, or turning thirty ceased to exist—if time were instead a net where every end is also a beginning, a sheet of paper that can be torn off and pasted elsewhere,

something soft and elastic that can be compressed and then unfolded—how could we understand the events of our lives? If “past” and “future” were not as solid as we believe, could we live differently?

For instance, if time were not linear, could we stop being the trembling walker on the tightrope? If it no longer has scales, could we not have to be like a counterweight, always trying to find our position in time?

-Ren Baiyu

Apple

Of all the works in the exhibition, Only Zhang Kailai's Apple directly engages linear time. It tracks an apple's decay— shrinking daily until it can shrink no more. The project began when her family member fell ill, revealing what she calls "an intensified withering process."

Daily photos compiled into video?

: These are scans, not photos.

Scanned daily with Polaroid transfers?

: Yes.

This is a work that lies between static images and dynamic images: the apple shrinks, becomes smaller and loses moisture. There is a tiny pause every few seconds. Such a pause allows us to observe how the apple changes from one state to another, and to something else. But at the same time, you will find that this process is almost unstoppable. You can only keep an eye on it, before you can fully see it, you are pushed to the next moment, then the next one, until the end - the process of shrinking is simultaneously accelerated and paused - it is paused just to continue shrinking

: I scanned once a day, except for the blank days in the middle. At some point in the video, you will find that it has suddenly become much smaller.

Initially, I didn’t notice the blank. At the time, she went back to China for a funeral and had to pausethe project. upon returning, she found the apple still shrinking and didn’t catch any mold, so she continued the project and kept the blank. Now, it transcended metaphor—real death merged into the images.

No medium is crueler than photography facing death—it's time's accomplice, merely watching and doing nothing at all. I think of Fukase's series Family: a series of family photos spanning eighteen years. At the beginning, you can see Fukasawa's wife. After their divorce, she no longer appeared in the photograph. Then the family welcomed a new baby, a beautiful little girl. A few years later, this girl died. Later, Fukasawa's father also passed away. When taking the group photo, family members held their portraits and everyone has aged a lot. Masahisa Fukase said, "My entire family, the image reflected on the frosted glass, will eventually die. This camera, which reflects their images and freezes them, is actually a device for sealing death.” He was almost saying, "All of us are going to die. Before that, let's take a photo together."

Photography can be time's accomplice—or ours. Apple touched me with its courage to collaborate with cruelty, where death is enveloped, "sealed," acknowledged—like the closure in WeChat. Loss in reality seems unavoidable, but conversely, when we admit it - even in photography - it also admits us at the same time.

Apple will be the first and last piece in the exhibition. We hope that everyone can enter from the cruelest part of time, see other forms of time, and then come out from there. I don't know if there will be any difference. I mean, perhaps the reality doesn’t change at all, but we can.

-Ren Baiyu

I still remember the first time I saw Wei Wentao’s work WeChat in 2019. It was hung up high, cascading down like a waterfall, and I kept looking up. It was a record of his long-distance conversations with his girlfriend. After they parted, he subjected their chatting page on wechat to long exposure in the darkroom, creating this work.

All the chat that you had?

: Yes.

How does long exposure work here? A screen recording?

: No, it was done in the darkroom. A phone was placed inside an enlarger, remotely controlled by another phone,

exposing the screen directly onto silver gelatin paper.

Sorry for the technical questions.

: No problem.

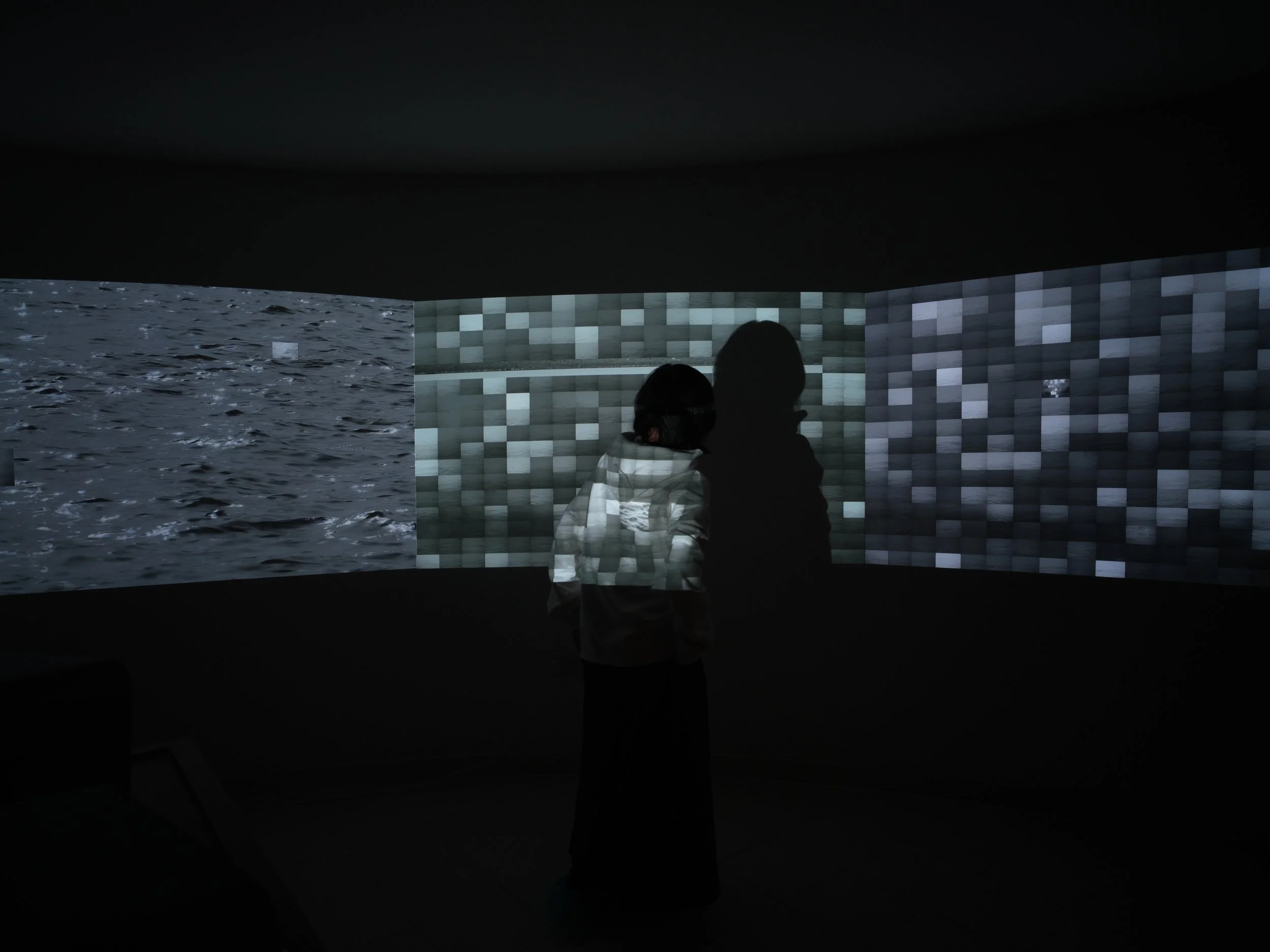

To me, the piece felt like a catastrophic car crash—a collision so violent that the people inside, their bodies, expressions, the conversation they were having, the food in their hands, their shared past, and their individual lives were all squashed in an instant. WeChat carries an inward violence, violence thatis able to compress three dimensions into two dimensions. With time extracted, joy and fights collapse into indistinguishable and uniform pixels,and what we call love ends up as a thin sheet—though one so dense it leaves you breathless when facing it.

Yet there’s also immense liberation here. In this work, the conversations are reduced but also preserved. Even the “end” becomes part of the image, doesn’t it? If, in reality, an ending of a relationship is a totalnegation—“what was once here is now gone, and we will eventually forget it”—in WeChat, the “end” appears at the bottom of the frame, perhaps as a conclusion, but it no longer erases what happenedbefore. Instead, it remains there, like every other moment, part of the whole—even acting as a border, barring new time from entering. Here, “the end” is no longer destructive; compared to loss, it feels more like completion. I often think about this piece, perhaps because of its violence, or perhaps because of its mercy.

-Ren Baiyu

Glisten

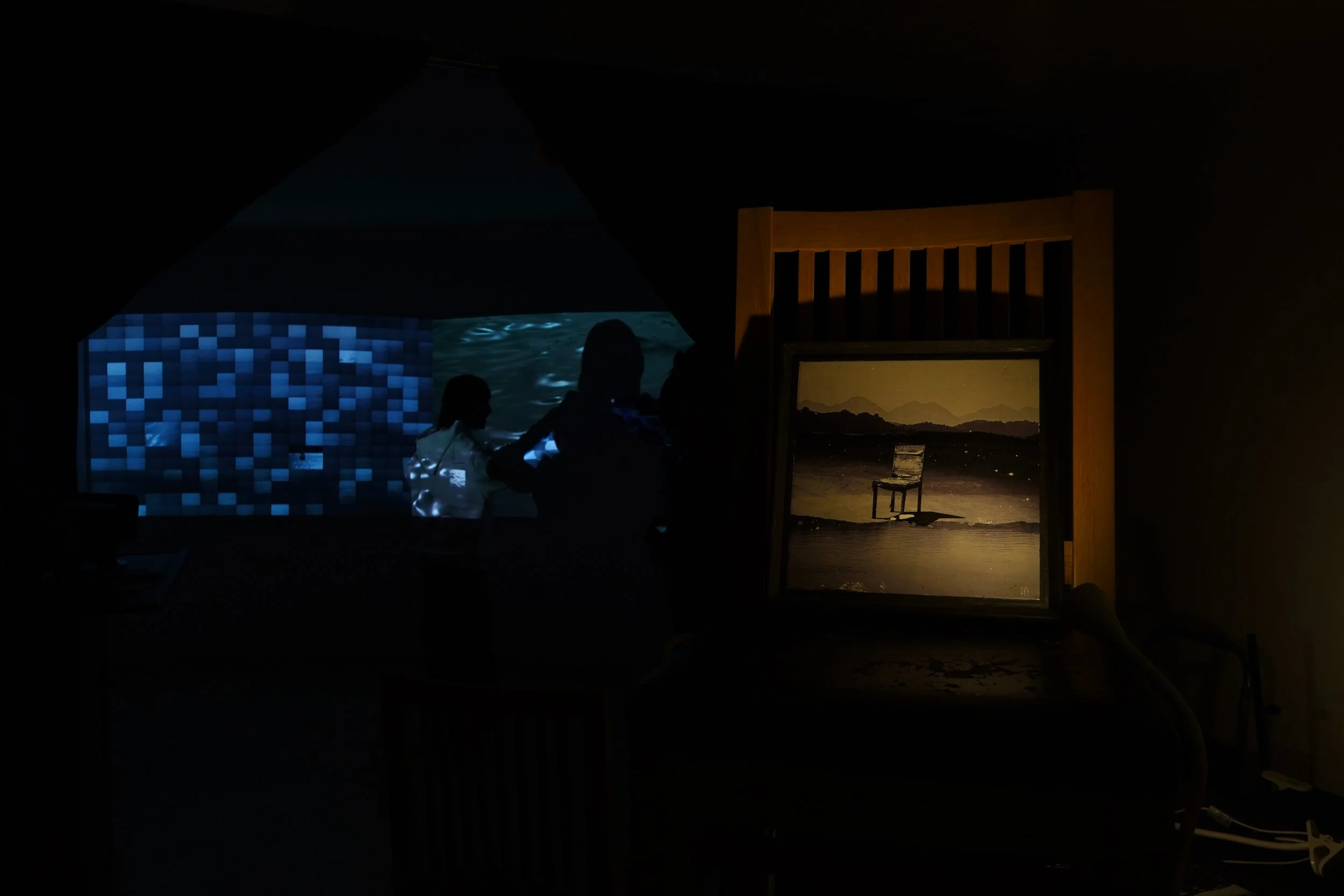

Shi Hui’s Glisten, on the other hand, is a work that is very expansive. If WeChat is an inward compression, Glisten is an outward expansion: Shi Hui filmed numerous videos of West Lake, juxtaposing them so that within a single frame, you might see many West Lakes—large and small, distant views and ripples—collectively forming the “essence” of the West Lake in her mind.

Why can’t a single video present West Lake?

: Whether a photo or a video, there’s always time embedded in it—an instant or longer. But to me, nature is a totality; it

has nothing to do with time. Using something bound by time to represent something that is timeless doesn’t make sense

to me.

I see. So these weren’t all shot at once.

: Right. They were taken over many visits, from different angles—some even from within the lake.

It reminded me of Thomas’s line in The Unbearable Lightness of Being: “What happens doesn’t count”. When we try to grasp the totality or essence of something, time limits us. Whether five minutes or a year, we can only capture a part of it. So Shi Hui has to lead us into the same water again and again, then, in her words, “weaves” them together. My friend Ma Xinyi and I both loved thisphrasing. Weaving—the word itself is plural, implying multiple threads emerging, intertwining, generating. Its structure resembles a dense net: add one strand of time, then another, then the humidity, temperature, and scent of that moment, until they stand side by side, diluting each other, forming a more complete pattern. Specific time dissolves into the whole, making a vast, multidimensional, boundless West Lake possible.

-Ren Baiyu

Chaos

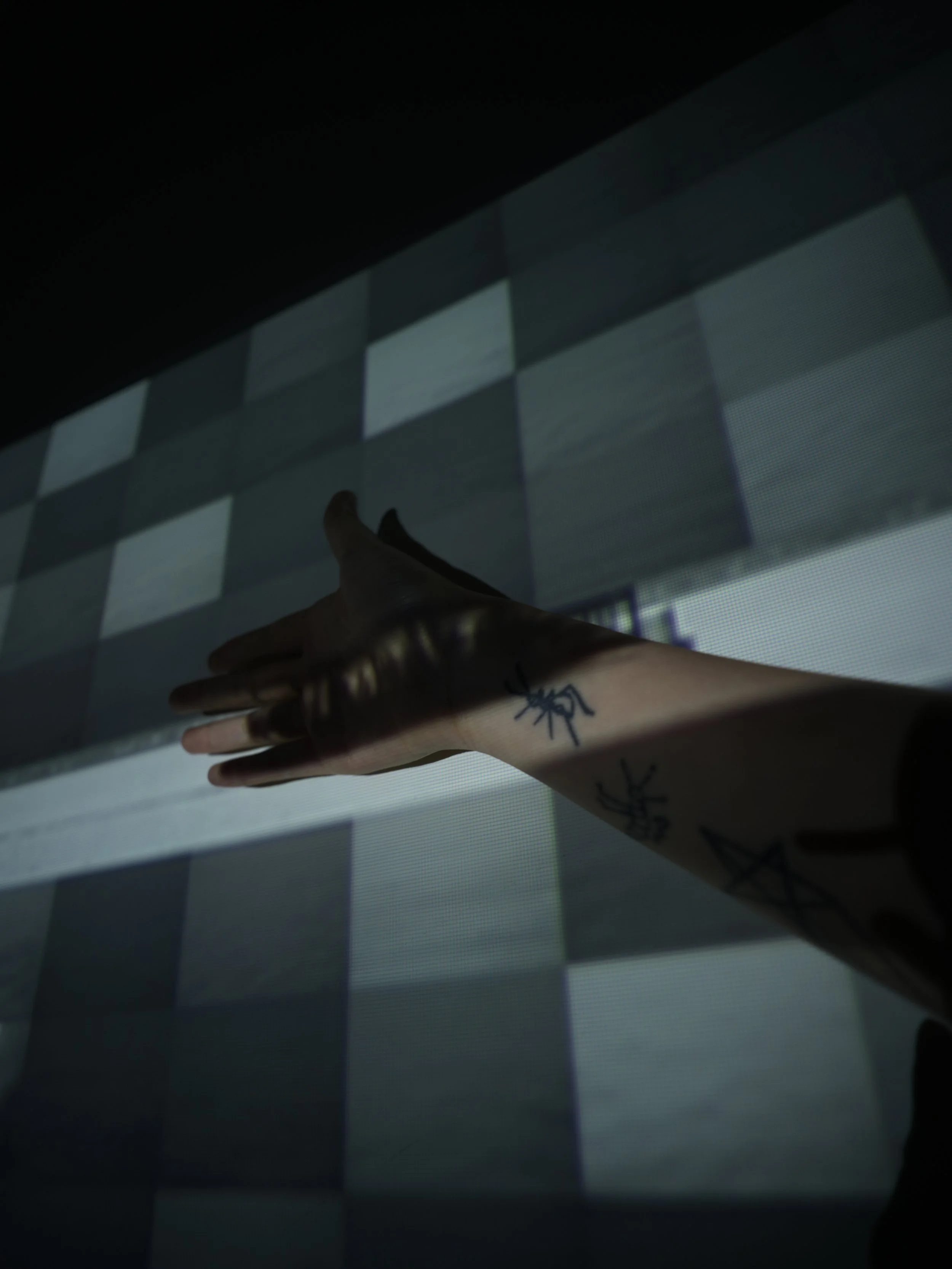

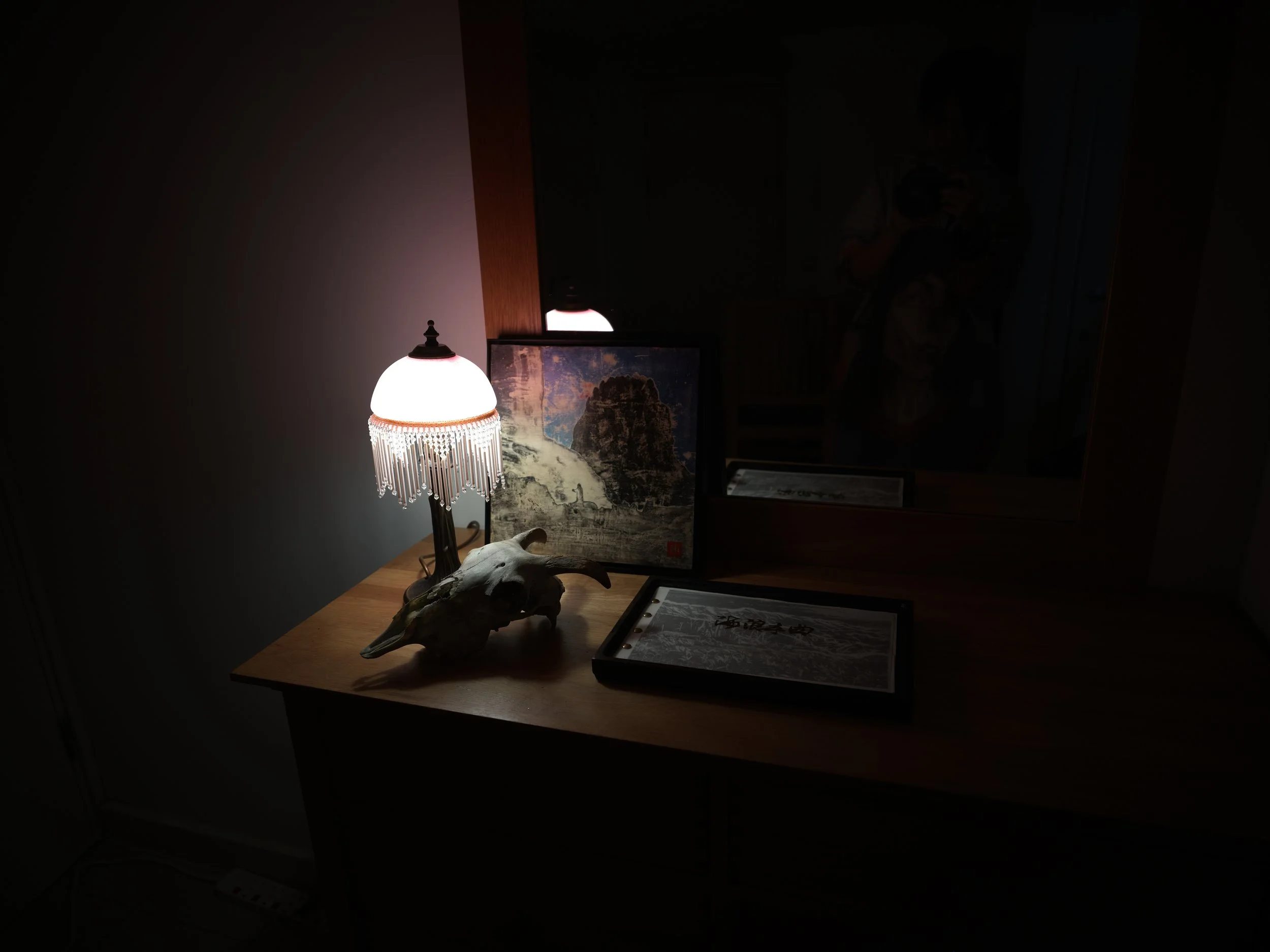

Like Shi Hui, Wang Xuehan works with collage, but he’s more like a mischievous child playing freely with time—a freedom born of his distrust in concepts like past, present, and future. Unlike Glisten, there’s no central subject (like West Lake) in his work, though landscapes often appear in his images. What matters isn’t what appears in his frames, but how they appear. To me, he’s only ever exploring one question: Is nonlinear storytelling possible? Each of his works is an answer to this theme. In his own words, he’s more interested in what happens outside of time. If a photograph captures a single moment, frames a single reality, his primary fascination is disrupting it—combining incongruous times and spaces, erasing the certainty to see what remains and what else can emerge. He tears fragments of time from one place and pastes them elsewhere, letting seawater flood a room, staircases hang midair, objects appear where they shouldn’t, creating new realities. Realities that before they materialize, seem impossible. This possibility of resetting remains at the core of Xuehan’s work.

: Time is interference in understanding the essence of things. When removing it, what’s left is the essence.

Yes, I think. Shi Hui said the same thing.

By “interference,” he means that within time, we only see the changing parts, not the parts that don’t change—like certain animals that perceive motion but not stillness, snakes for instance. In other words, in front of the essence of things, we’re often blind. If Glisten approaches wholeness through repetition, Xuehan’s work achieves it through juxtaposition: on one side, the fleeting theater of the Anthropocene; on the other, the eternal quietness of mountains, sea, and moonrise. A dining table under a tree is neatly set with plates and cutlery—for humans, or for gods. Nature is eternal; it’s us who shift like the stars. In Xuehan’s work, the order of reality has never seemed so fragile. This isn’t about imagination but a determination to test the essence of things in chaos.

-Ren Baiyu

“What Time Is It Now?”—An Exhibition Experiment at Home Comes to a Close

We would first like to express our heartfelt thanks to curators Ren Boyu and Ma Xinyi for their professional support and wholehearted dedication throughout the exhibition process. For our still-growing team, this project has been an invaluable learning experience.

Over the past year, we encountered many uncertainties: from time zone differences, to discarded plans, to artwork nearly being held up at customs—moments that brought the exhibition to the brink of cancellation. But obstacle after obstacle, we moved forward. Precisely because of these setbacks, this outcome feels all the more meaningful. We are deeply grateful to every team member—and to our own bit of good luck.

Our sincere thanks also go to the four participating artists: Shi Hui, Wei Wentao, Wang Xuehan, and Zhang Kailai. Thank you for your trust, your collaboration, and your generous professionalism throughout the preparation of this exhibition. Your works gave our “home” a distinct language, opening up four temporal dimensions within the ordinary rhythms of daily life.

We’re also truly grateful to everyone who visited, supported, and engaged with the exhibition. Your presence and your ways of seeing made the show whole. To those who shared feedback—thank you. Your thoughts and responses have provided us with experience to carry forward into future projects.

Thank you, from all of us, for your collective support. We’ll see you in Chengdu this August.

—The MoMingTang Team